Art restitution case that was never made

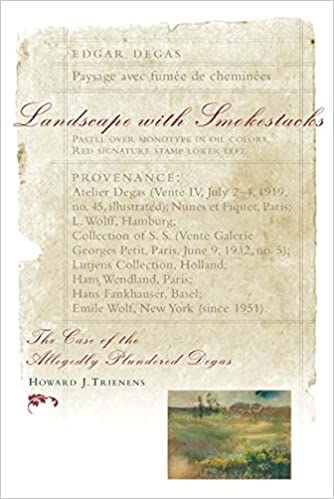

Landscape with Smokestacks: The Case of the Allegedly Plundered Degas

by Howard J. Trienens

2000, Northwestern University Press

Many (most?) civil art cases never go to trial. At some point before everyone gathers in a court room to make their case, the parties involved agree to settle the case in some way. This is probably good because court cases are expensive for everyone, and (in theory) a settlement can be a lot more creative and even satisfying than a black/white court judgement. That said, there are at least two drawbacks to a case not going to trial. First, various points of contention within the law regarding art are not tested, leaving an ambiguous grey space that awaits clarification. No precedent is set and we have nothing to apply to similar cases. Second, the vast amount of research conducted by the legal teams of both the claimant and the defendant often just sort of vanish into the aether. When the lawyers don’t get to make their case in court, we don’t get to see what their case was.

“Landscape with Smokestacks” by Howard J. Trienes is a response to that second issue. In this book, Trienes, who was the lawyer for the defendant in a high profile case concerning a Degas, makes the case he never got to make in court. He lays out his argument in a quick 100-page read, I suppose to preserve it and to not let that work end up filed away in a cabinet somewhere, future paper shredder fodder. I rocked through it in a couple of hours and found it worth that time. What I great idea! I wish this was done for every case. Yeah, yeah, who pays for the time of compiling it, but still.

I suppose in my ideal world, this book would be in two parts. One would be Trienes case, the other would be the case for the claimant prepared by their team headed Thomas R. Kline. Indeed, Trienes ends this book by asking the reader to be the judge and “draw your own conclusions”, yet how can we with only Trienes’ argument? Trienes would likely counter that Kline’s argument was presented via the media, but TV sob-stories are a far cry from the kind of documentary research that goes into prep for a lawsuit. I acknowledge that the reality of two sides in an art dispute coming together to, well, present two sides of an art dispute is unrealistic (particularly if relations went sour along the way), but I can dream, right?

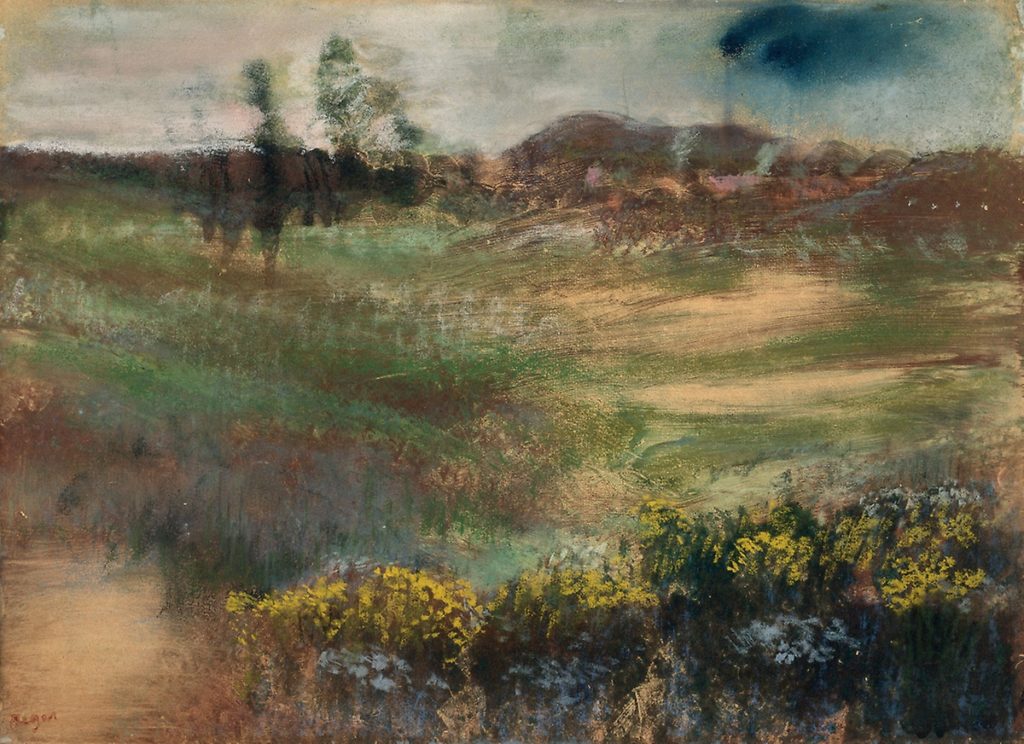

The case! The case concerns a Degas monotype called Landscape with Smokestacks that was owned by Friedrich and Louise Gutmann, Dutch art collectors who were killed in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz respectively. Their art collection met a predictable fate for assets held by people the Nazi’s classified as Jewish. The Gutmann’s children, Bernard (who was a British citizen and who changed his name to Goodman) and Lili attempted to recover the Degas and other works of art, with some successes up in to the 1950s. By the 1990s, Bernard Goodman’s children, Simon and Nick Goodman had taken up the case of finding missing family art. You’ll recognise Simon Goodman’s name as the author of the book The Orpheus Clock, which I reviewed positively here: https://www.anonymousswisscollector.com/2015/09/the-orpheus-clock-by-simon-goodman.html

So okay, Nazi looted art should go back to heirs, seems easy. However, theirs a twist. Trienes argues, via “Landscape with Smokestacks”, that the Gutmann’s no longer owned the Degas by the time it ended up in the hands of a Swiss dealer with suspicious ties to wartime art profiteering. While, yes, some pieces from the Gutmann collection can be shown to have ended up in, for example, the collection of Hermann Göring (not…good…), there’s no solid evidence that the Nazi’s seized this Degas. And even if it turns out they did, Trienes argues that there is no evidence that Gutmann, who had consigned the piece to a Paris-based art dealer for sale, even still owned the piece at that point. He argues that the scant documentary evidence in existence shows that the Degas was sold by the dealer, and that if the Gutmann family never got the money from that sale, French law would not support recovery of the monotype as it would have been sold correctly and purchased in good faith, rather the Gutmann case would be against the dealer they consigned the monotype to.

Trienes sure makes his case here, but, again, the other side is missing here. The author’s summary of the claimants’ case, understandably, is through the lens of someone who has spent a considerable amount of time opposing it. Important points in favour of the claimants go unmade and assertions go unchallenged. Such as (thinking through my fingers here):

- If the piece was sold, where is the proof? Absent any document recording sale, shouldn’t we assume it *wasn’t* sold and was swept up by the Nazis along with other Gutmann pieces?

- Even if the piece was sold, what was the duress level of the sale? And I’m thinking about the dealer they consigned the piece to, who was Jewish…even if the Gutmann’s didn’t consign the piece under duress (and, of course, they may have), was the piece then sold under duress?

- The defendant’s responsibility to conduct proper due diligence into the provenance of an artwork is at least as important, if not more so, than the claimant’s responsibility to have conducted the right research so as to locate the artwork in a timely manner. Anyone who buys artwork without rock-solid, totally clear provenance through the 1930s and 1940s can be characterised as not having achieved a minimum standard of due diligence before their purchase.

But, again, this case was settled, and it was settled in a way that would be impossible via the court. The monoptype was sold/donated to the Art Institute of Chicago for a price determined by external appraisers. The defendant received a tax break for half the value and the Art Institute paid the Gutmann’s for the other half. Trienes cites the growing costs of litigation and the feeling on both sides that it wasn’t obvious who would win as reason why the settlement occurred, describing it as an arrangement that pleased no one except the Art Institute of Chicago.

The “credit line” for the piece at the museum reads: “Purchased from the collection of Friedrich and Louise Gutmann, and gift of Daniel C. Searle“.