Reflecting on a broken ‘Easter Island Head’ replica, cultural loss, and return.

Wellington New Zealand has an Easter Island ‘head’. It isn’t very big. It isn’t very real. But the concrete replica has been proudly looking out from the banks at Lyall Bay since it was gifted to the Kiwis by Chile (which is where Easter Island is, so to speak) in 2004.

Moai with bodies facing inland at Ahu Tongariki by Ian Sewell

For the record Easter Island is really called Rapa Nui; the heads are really called moai; the moai aren’t even just heads, they have bodies; they are also meant to face inland, not to the sea. Whatever. Wellington had one until yesterday some kids knocked it over. Now they have one in two pieces.

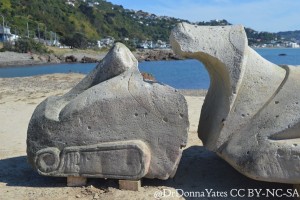

As it just so happens, I am in Wellington at the moment and, not one to miss an opportunity to ‘investigate’ some ‘heritage crime’ (read: take some weird photos of an artfully, painfully broken Easter Island head), I rushed down to Lyall Bay yesterday morning to take a peek at the mutilated moai before the fix-it crane came to take it away.

Photos, photos:

Thankfully this wasn’t just a gawking session before brunch. Pondering a vandalised fake moai gave me a chance to ponder the real ones.

The rise and fall of the moai

The people of Rapa Nui, who are Polynesian like the Māori of New Zealand hence the head gift, only built the moai for about 250 years or so from 1250 until 1500. They stopped because they felt like it, or ran out of trees needed for transporting, or some combo of the two. Then they knocked them all down sometime after 1722, probably for much more significant reasons than these Wellington kids did.

All told, they made 887 moai of various sizes; some are incomplete and still in the quarry. They were important. They were powerful. They were likely bursting with mana, Polynesian spiritual umph.

Obviously they’re awesome. Europeans were all over them. They wanted those heads.

Yet the moai are pretty huge and extremely remote. Rapa Nui is sometimes considered to be the most remote place that humans have inhabited. The Rapa Nuians, who came to the island on massive sea canoes, traveled 2,600 km minimum to get there. The closest inhabited bit of land to Rapa Nui is Pitcairn Island, currently hosting a population of about 56 people, the descendants of the Bounty mutineers. The Polynesians of Pitcairn, by the way, had totally exhausted their resources and died out by the 1400s. Rapa Nui was on that path too.

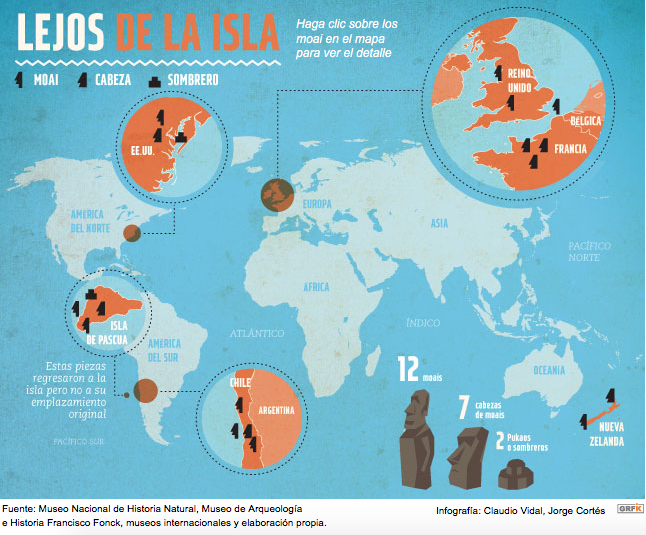

The point is that even a motivated 18th or 19th century European collector dying for a moai would have to arrange to have a massive stone thing floated all the way home from, literally, the middle of nowhere. Out of 887 moai, only about 6 to 11 were stolen. Also some bits and pieces. Pretty good, all things considered.

- Hoa Hakananai’a being moved at the BM.

- It isn’t easy to move a moai.

Hoa Hakananai’a (Stolen Friend)

The hunted heads

The aptly-named Hoa Hakananai’a (Stolen Friend) was the first moai taken from the island. He was taken by the crew of the HMS Topaze, a British Royal Navy Ship, in 1868 and about 9 months later made it to London where he was, of course, installed in the British Museum after being offered to Queen Victoria. Until WWII he was kept outside but was pulled into the museum to reduce the possibility of him being bombed. There he still sits, really far from home.

After that, others succeeded in hauling a few away. There are complete moai in collections in Santiago (obviously), Brussels, London (x2), Washington DC (they have a head and other bits too); a few heads in Paris; a head and a trachyte in New Zealand (NOTE THIS). Plus there are a lot of fakes out there.

Rapa Nui would like the real ones back, please.

Limited success

Some have come back home. In 2006, a 7-footer, gone since 1929, came back to Rapa Nui. The statue was presented to Chile’s then-president, sold to a collector, moved to Argentina, sold to another collector, shipped to the Netherlands, shipped back to the Argentina when collector 2 didn’t pay, and spent years in Argentine customs.

Basically, the statues are what Rapa Nui has. That’s about it. By the time Europeans arrived, Rapa Nui was already in a bad state: society was crumbling due to extreme over-exploitation of resources. In the mid 1800s, half the island’s population was nabbed by Peruvian slave traders; the kidnapped people had to be returned, sure, but they brought smallpox with them. Then TB came. Then Europeans who bought up all the land. By 1877 only 111 people lived there; 97% of the island’s population gone within a decade. 36 of those 111 had surviving children and all of today’s Rapa Nui (60% of the island’s population so just under 6000 folks) are descendants of those 36. The term “cultural loss” seems too weak to describe this situation.

But they’ve got those moai. Come and see them.

Tourism and cultural survival

So we have a situation of spectacular cultural florescence, followed by near cultural collapse, followed by cultural resurgence centered around the income that can be generated from cultural tourism. By this I mean that people don’t have to not be Rapa Nui for economic reasons because there is a viable economic way to totally embrace their traditional culture and much motivation to push for renaissance. Rapa Nui needs those statues to survive spiritually and financially. Tourism is the island’s primary source of income. Statue tourism.

But, you might say, having a couple of moai in France or Washington DC means more people can see them. That’s good, right? Well think of it this way. Rapa Nui needs tourism money. They don’t need to be undercut by so-called universal museums that they have no hope of ever visiting. It isn’t like France or DC sends any of their stuff to Rapa Nui. Shouldn’t Rapa Nui decide where their ancestors reside?

Keeping foreign cultural objects while demanding yours back?

So coming back to the idea of a few moai bits being in New Zealand. Understand, I don’t know the situation. They could be here with the permission of Rapa Nui. But if they aren’t, recall that New Zealand’s Polynesian people lost a lot of their culture pieces to European curio collectors. They have also been incredibly successful at getting some of the more significant stolen things back, notably toi moko: tattooed and preserved heads. Te Papa, the national museum of New Zealand, even has a repatriation programme and a hall to welcome objects and ancestors who have returned. Why, then, does a country that wants its own stuff back have other folks’ stuff?

I honestly have no idea how they logic that one out.

Te Hono Ki Hawaiki, which means Link with Ancestral Homelands. Te Papa’s repatriation hall.

I want to see Hoa Hakananai’a back on Rapa Nui.

I want to see the concrete replica back on the shores of Wellington in one piece on a more secure base.

I want a lot of things. The return of cultural objects is so very complicated. Perhaps more complicated than it should be.