The controversy surrounding the bankruptcy of the city of Detroit and the outside possibility of selling the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts has gone strange. Peter Schjeldahl, a commentator for the New Yorker, said DO IT. The interwebs exploded. Then the commentator said, never mind: DON’T DO IT. In his second article, Schjeldahl went a bit poignant:

The principle of cultural patrimony is indeed germane, and it should be sacred.

I agree, Peter, I agree. Which is why I wonder why very few people are calling the DIA out.

I have mostly been grumbling about the DIA situation on twitter. As everyone rushes to save Detroit’s bastion of culture, I fear that most are forgetting that the DIA has a history of some outright terrible acquisitions of very illicit antiquities. When I think of how past DIA curators etc have approached the illicit antiquities trade, their falsehoods, their lies, it makes it hard for me to feel sympathetic to the museum. I am truly sorry that the people of Detroit are stuck with a museum that was once so willing to buy terrible things and I am sorry those things are now in the “public trust” of Detroit (although, of course, the countries of origin would disagree); but I am the most sorry that in the theoretical situation where Detroit’s art collection gets offloaded, these antiquities might be sold on.

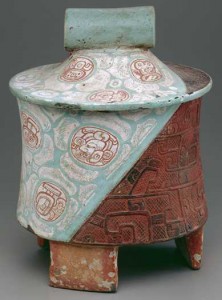

One object in particular is quite special to me: a vase from the spectacular Guatemalan Maya site of Río Azul which the DIA houses illicitly.

This is the vase:

Not awesome.

I take the looting of Río Azul quite personally. As a young, naive archaeology student, my head filled with the glory of the past, it honestly did not occur to me that anyone would loot an archaeological site. Not these-a-days. In my second year I took a course called Maya Cities taught by Norman Hammond. Not only did the course drastically change my archaeological focus (would you have thought? I was focused on Egypt before that!), but it introduced me to looting as a devastating confluence of beauty and greed. The first photograph of looters trench I ever saw was a looter’s trench at Río Azul. It was likely the trench that produced the vase that is in the Detroit Institute of Art.

Furthermore, when I was on my first extended bout of fieldwork working at the VERY heavily looted site of Holmul, Guatemala, the local workers told me that Río Azul was being looted RIGHT THEN. They also said the people doing it were dangerous and had killed people before. I now think they were talking about the looting of the Cancúen ballcourt marker, but I was young and terrified at the thought. The vision of those emptied tombs haunted me. The idea of people being killed over this was terrible.

If you want to talk about being in bed with bad people, one of the other objects thought to have come from the same incident of looting is a striking jade funerary mask. The mask disappeared into the Barbier-Mueller collection (yes, THAT Barbier-Mueller collection) never to be seen again after Guatemala made a failed attempt to claim it in a Spanish court. The mask also passed through the hands of the man who sold the vase to the DIA: Peter G. Wray.

In my article on the jade mask, I go through a series of steps why we know for certain that the mask (and the pot at the DIA) were looted from Río Azul and why they are the property of Guatemala:

- The Maya were a literate culture; an inscription on the back of the mask bears the emblem glyph of Río Azul and the name of a ruler sometimes rendered as Zak Balam or Sak Balam (White Jaguar), also called Ruler X or Governor X.

- Due to the complex nature of the language, a grammatically and contextually correct Maya inscription is nearly impossible to fake; the mask is not considered to be a forgery.

- Zak Balam’s name and image appear on Stela 1 at Río Azul, a monument that is still at the site, confirming he was a ruler of that polity. The date on that Stela is 26 March 393 AD.

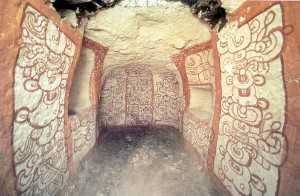

- The looted Tomb 1 in structure C-1 at Río Azul was an elite tomb. The date 9 September 417 AD is painted on the wall of the tomb in a context that would closely align with the symbolic birth of the individual interred there into the next world, in other words his death.

- Both the dates and matching water/swamp mythology iconography, would allow for the individual mentioned on the mask and Stela 1 to have been buried in Tomb 1.

- Maya masks are typically found in funerary contexts associated with the individual that they depict or name.

- Tomb 1 had not been looted in 1962 when the site was visited by Richard E.W. Adams.

- Tomb 1 had been looted in 1981 when Ian Graham visited the site.

- Guatemala claimed ownership of all archaeological remains, even undiscovered remains, in 1947 via Article 1 of Decreto No 425.

- The mask was not seen on the art market or in a private or public collection until the early 1980s.

So what have past DIA folks had to say about this?

When asked by the Philadelphia Inquirer about the possible looted nature of this vase and others purchased from Andre Emmerich Gallery, Sam Sachs, the director of the Institute from 1985 until 1997, issued the following statement:

We do not know from what site these vases come. Had we thought they came from a looted site, we never would have acquired them. The [institute] bought them in good faith and on the firm representation of the owner to hold us harmless and that the piece was legally imported into the U.S. … It is our policy and the policy of UNESCO and the U.S. government that we will not knowingly buy or cause to be bought any stolen, illegally exported or imported objects.

Interesting assertion, Sam. The vase has the name “Six Sky” on it. Tomb 12 at Río Azul belonged to Six Sky. See above. Hmm. I think this statement is lacking in even a small dose of honesty.

Let’s see what then-curator of African, Oceanic and New World Art Michael Kan had to say when asked if the DIA required any export permit documentation proving the item was legal before purchasing the piece:

‘Oh, heavens no. Who has time to do that? We’re very busy people here. I don’t know what that’s like. It’s like asking people if they check out every vitamin that’s in a capsule’ (Michael Kan, quoted in Salisbury 1986).

THERE it is. The truth.

So getting back to the point, if the Detroit Institute of Art really is operating on behalf of the people of Detroit and if the items they have acquired are held in the public trust, the people of Detroit have, yet again, been hosed by corrupt people in public positions. They took money that could have gone elsewhere (exchanges? local archaeology? support of contemporary Detroit artists?) and blew it on very terribly looted antiquities. More specifically, they blew it on looted antiquities that I care about.