OR Carl Sagan breaks it down

When I was an undergrad I was lucky to get in on the ground floor of a course taught by Curtis Runnels that was devoted to pseudoscience and claims about the past. I honestly think it may have been the most useful course I ever took.

First, it showed me that not everyone naturally approached information with a healthy dose of skepticism. That others don’t think the way that you do is a shocker for any 19-year-old, but to find out that it wasn’t automatic for people to weigh evidence based on some sort of internal believability scale went a long way towards explaining the weirdness of the world for me. Up until that point I couldn’t fathom why anyone would come to the conclusion that, I don’t know, space aliens built the pyramids. Afterwards I could see the divergent lines of approach and evaluation, not to mention sinister tricks and teases. I stopped blaming people for being uninformed or ignorant.

Second, the class taught me that it was worthwhile to both develop a way to talk to people about these issues and to let it slide when an argument about such a topic doesn’t matter. It is not worth treating people like they are stupid or dismissing their beliefs based on something so silly as your academic expertise, especially if you are at a boring cocktail party and the person brought up crystal skulls because they were just trying to be nice and relate to your work. It is worthwhile to push for better reporting in the media but you need to not sound like a dusty old ivory tower occupant and play into their game. Etc. etc. I could rant on…

It bothers me that undergraduates are not taught how to evaluate the merits of a scientific or pseudoscientific claim as a standard part of the first year of their education. They arrive on the university scene, bright eyed and bushy tailed, ready to regurgitate the things that they read, hopefully laid out in a well structured essay. In the limited teaching experience that I gathered at Cambridge, this deficit was striking. These kids were brilliant, many of their essays were so good, but only a few of them had developed a sense for questioning all-too-easy conclusions offered by other scholars OR the ability to keep their cool when a person (or culture) truly believed something that was non-archaeological (picture me, my face in my hands, as a student actually argues about “reality” and archaeological “truth” with a Canadian First Nations leader who was lecturing on his cultural views of the past).

Because of the deficit, I started asking my students to go through Carl Sagan’s Baloney Detection Kit from the book The Demon-Haunted World. I first read this as part of Runnels’ pseudoscience class and it helped the young me put the pieces together (“wait” said young me “people don’t automatically know this stuff?! Oh!”). For the students who had never learned how to evaluate claims, this would blow their minds; for the students who could evaluate claims, perhaps just thinking this through would bring them further down the path of dealing with hypocrisy, developing ways to be polite and constructive (not belittling and useless), and accepting that nothing is black and white.

I feel so passionately about this that I have managed to slip this into what I hope is the standard archaeology curriculum for English speakers at least. For the past few years I have been producing a lot of the material that comes along with the textbook Archaeology by Renfrew & Bahn. In a series of activities that I developed for the book (and which now appear to not be freely available online but just to users of the textbook, sorry guys), I have students evaluate claims about the Bosnian “Pyramids” after reading through Sagan and thinking about Occam’s Razor for a bit. If they get it nowhere else, they will get it from me.

So why am I writing this in an illicit antiquities blog? Lately I have been revisiting quite a few well known cases of looting and smuggling, etc, which leads me to do quite a bit of out-loud exclaiming. My lovely boyfriend tends to ask what is up and I tell him. I suppose this might be the first time I have gone into detail about certain things. I showed him some pieces in the George Ortiz Collection that Ortiz states openly are from the site of the famous Malagana Hacienda looting of 1992/1993. The fella asked how he can possibly have those if the Malagana culture wasn’t known about until the looting, how? And I had to tell him “prove it: what if those pieces were made by the Malagana culture but traded to another culture that was nearby, and then deposited in a grave from that culture and then discovered in, I don’t know, 1803 and taken to Europe then and passed, unrecorded, through the hands of various collectors and into the collection of George Ortiz?” Sure, that is crazy, that is insane, that is nearly impossible, but I had to tell him that arguments like that are the norm.

So why am I writing this in an illicit antiquities blog? Lately I have been revisiting quite a few well known cases of looting and smuggling, etc, which leads me to do quite a bit of out-loud exclaiming. My lovely boyfriend tends to ask what is up and I tell him. I suppose this might be the first time I have gone into detail about certain things. I showed him some pieces in the George Ortiz Collection that Ortiz states openly are from the site of the famous Malagana Hacienda looting of 1992/1993. The fella asked how he can possibly have those if the Malagana culture wasn’t known about until the looting, how? And I had to tell him “prove it: what if those pieces were made by the Malagana culture but traded to another culture that was nearby, and then deposited in a grave from that culture and then discovered in, I don’t know, 1803 and taken to Europe then and passed, unrecorded, through the hands of various collectors and into the collection of George Ortiz?” Sure, that is crazy, that is insane, that is nearly impossible, but I had to tell him that arguments like that are the norm.

Basically, multiplied hypotheses are allowable in this area and to invoke Occam’s Razor often does little good. To come up with a “what if”, no matter how complex, allows for a dismissal of the most simple, uncomplicated explanation.

It just seems to be the theme of the week: complicated, multiplied hypotheses being treated like they are of any merit or value.

Complicated Explanation: The argument that if a law is not in the UNESCO heritage law database, than the law is obscure or obsolete and should be ignored by courts.

Uncomplicated Explanation: The UNESCO heritage law database is totally voluntary and some dude just didn’t upload every law.

Complicated Explanation: There is no REAL way to tell which Moche site this object came from, even if it looks exactly like a Sipán object because maybe the Moche traded stuff around or maybe the same artist made stuff for different sites, and thus there is no way to tell if this REALLY came from the famous looting of Sipán, even if it did appear on the market around that time, being sold by people who admit to have been involved in all of that.

Uncomplicated Explanation: That thing came from Sipán.

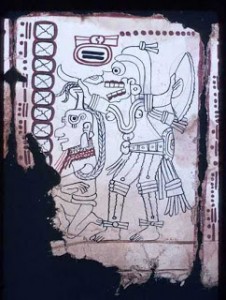

Complicated Explanation: I possess this Maya codex because some mysterious person called me and I agreed to get in a small aircraft with them and fly to the middle of nowhere to some airstrip in México where some peasants with guns showed me the piece and then let me take it back with me, without paying for it yet, to get it authenticated, but I don’t know who any of those people are or where they found it. (Seriously, this is constantly repeated in the literature).

Complicated Explanation: I possess this Maya codex because some mysterious person called me and I agreed to get in a small aircraft with them and fly to the middle of nowhere to some airstrip in México where some peasants with guns showed me the piece and then let me take it back with me, without paying for it yet, to get it authenticated, but I don’t know who any of those people are or where they found it. (Seriously, this is constantly repeated in the literature).

Uncomplicated Explanation: (A) It is fake and I am making up a sexy story to help sell it; or (B) I know right where it came from but I don’t want archaeologists to know.

I could go on and on and on, of course, but I keep stumbling back to the idea of believability. I tend to think that no one, NO ONE believes any of that crap, that it is entirely fabricated so that greedy terrible people get what they want. That idea is infuriating (and oddly motivating). Yet, thinking about it, I wonder if there are people who truly believe this stuff, who don’t have a solid skepticism foundation, who frankly are not as smart as you and I and can’t really get there on their own. I suppose what I am trying to say is that I need to not just look at these claims as a thin veneer over total deceit, but as points that someone, somewhere thinks are “fair”. To come at them not with an explosion of accusatory anger, but in a more productive way.

Here’s to figuring out what that productive way might be!