Not everyone owned paintings, but everyone owned books…and they were looted by the Nazis

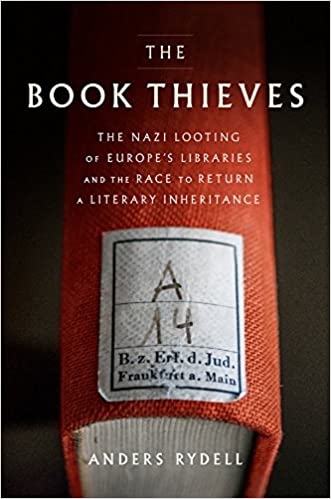

The Book Thieves: The Nazi Looting of Europe’s Libraries and the Race to Return a Literary Inheritance

by Anders Rydell (translated by Henning Koch)

2017 [English Edition], Viking

Everyone talks about Nazi-looted art. At least one Nazi-looted art case makes headlines around the world every week. There’s at least two going on as I write this [note, posting this with a few week delay]:

- Spanish museum can keep Nazi-looted Pissarro painting, US appeals court rules

- Hunt is on for rightful owner of Nazi-looted French painting

As the author of “The Book Thieves”, Anders Rydell, notes art is flashy and expensive. Big price tags bring media attention. Yet $40mil Pissarro’s make up only a tiny fraction of the cultural heritage that was plundered and destroyed in Nazi and occupied territories. Furniture, silverware, dinner services, and of course books were also sucked in to the vast looting machine, taken from the homes of regular people. They were boxed up and sent off in one direction while their owners were sent off in another, most often to their deaths. These millions of books ended up in libraries across Europe, most with no indication of who owned them. They are silent witnesses to horror…and may be the only physical trace left of their murdered owners.

In January I moved to the Netherlands. It is my first time living in a place that was occupied by the Nazis. Maastricht fell in May of 1940, and was the first Dutch city liberated in September of 1944. In between those dates, the city’s Jewish population was murdered, and their possessions were seized. Among the people murdered were a Jewish couple who lived in the house next to mine.

I know very little about these people, just what is online at https://www.joodsmonument.nl/. They were in their 60s, the husband sold ladies hats, they were killed in June of 1943 in Westerbork, seemingly along with the wife’s elderly parents. They had no chance really. You can just about see the official residence of the Beauftragte from the doorstep of our houses. It’s at the end of the street. See photo. I think about that couple often. I think about them dropping in to my house for a chat with their neighbours. Walking my floors. Sitting in my garden. And I think about the people who lived in my house at the time…people who were not Jewish. How did they react when their neighbours were taken away or fled?

Now, having read “The Book Thieves”, I think of my lost neighbours again. I live in a nice part of Maastricht, but our two houses aren’t particularly fancy. They aren’t the kind of houses that would be stuffed with Pissarros (although our other neighbours’ houses could have been and, maybe, are), however they certainly may have had books. Books that were loaded up, given to libraries, sold, left to rot in barns, pulped, or burned. Little literary pieces of my neighbours may be in a random library somewhere, just waiting for their story to be told.

I found Rydell’s account of the Europe-wide looting of books by the Nazis to be both meticulously detailed and moving. Structured around a series of locations of lost libraries and archives, “The Book Thieves” outlines the whole of the Nazi book looting operation, from its theoretical underpinnings to the counter-looting done by a devastated Russia. While the author focuses primarily on major library and archival collections held by Jews, Freemason, and Socialist groups, personal stories are woven in to each chapter because books are so very personal.

At one point in the text, a person he quotes notes that books make us human. By depriving people of their books, the Nazis further deprived people of their humanity. In addition, the Nazi’s sought to collect and archive material from the groups they were targeting in order to study their enemies. They made vast archives filled with Jewish, Freemason, and Socialist books and documents with the goal of creating quasi-academic research institutes. Not only did they Nazi’s steal these books from these groups, they stole the ability to protect, define, and interpret the groups’ histories. Dehumanising again. After dehumanisation, next stop is mass murder.

Stolen books often took a different pathway through the Nazi machine than artworks, and as such most everything in “The Book Thieves” is new to me. Even if you’re someone who has read every book there is on Nazi-looted art cases, you are likely to learn something you didn’t know in “The Book Thieves”. If nothing else, the sheer amount of displaced books will startle you…it can’t not. Rydell’s book is worth your time.

While “The Book Thieves” ends with a poignant book return, I want to end on the task at hand. Throughout the book, Rydell interviewed numerous librarians and archivists who spend their days slowly inspecting massive book collections for volumes that may have been looted by the Nazis. It is hard work, but I imagine the investigative aspect of it is interesting, and the knowledge that you are helping to put right something that was so wrong must be satisfying. As it just so happens, I saw two book provenance researcher jobs open in Frankfurt recently. Perhaps this is a sign that more funding is being devoted to this issue.

With every ex libris identified, with every library number matched, we are move a little bit closer to what the world should be. Books have been ignored for too long.