In this post I will present two stories about one Maya vase: what we would have thought if the vase was looted and what we know because it wasn’t.

When an artefact is looted its archaeological context is lost and, thus, our ability to learn about the ancient past from the piece is either greatly reduced or totally obliterated. When scholars try to reconstruct contextual information about looted artefacts, they risk making up stories that have no ties to reality. Looted artefacts introduce false information into what we know about the past and rob us of our ability to learn about our heritage.

Back in 2007 I used this example to discuss context loss for an undergraduate course I was teaching at Cambridge. A few years later I randomly ran into one of the students from that course in another country, both of us out of context ourselves. She told me she still remembered this vase, this example, and that for her it was the most memorable story from the course. In honour of my return to Belize, I’m giving the story to you too.

I’m not the first to use this vase to illustrate this point. Dorie Reents-Budet, no doubt, uses this example far more elegantly than I do in Painting the Maya Universe (1994), but I don’t have access to it at the moment. You’re stuck with just me!

Exhibit A: The Vase

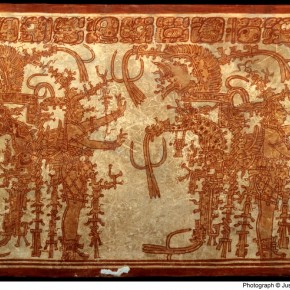

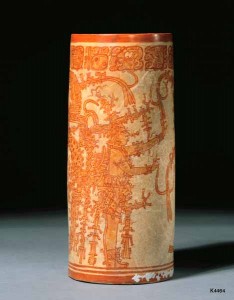

Tall and elegant with a gentle swell around its middle, this is a gorgeous classic Maya vessel. A study in oranges and creams, the vase is in the so-called Holmul dancer style, named after a similar pot found at a Maya site in Guatemala. Hundreds of looted Holmul-style vessels have appeared on the international art market. It portrays two individuals in regalia that is so far beyond elaborate: their vestments are downright mythological. Both figures are the Maize god. His back-rack is a model of the Maya universe: a celestial bird on a sky band, a cosmic dragon and a waterlily jaguar, a sacred mountain. Above is a band of hieroglyphs that states that the vase was made for Lord K’ak-Til, the divine lord of Naranjo (an ancient Maya city in Guatemala), and that it was meant to hold fresh cacao beans. Quetzal feathers sprout out in all directions. The Maize god’s fingers move almost musically. From his nose and mouth comes divine breath.

Analysis 1: If the vase was looted

Looted Holmul-style vessel in the Art Institute of Chicago listed as ‘vicinity of Naranjo’. True or false?

Say this vase appeared, without any archaeological information, as a looted and trafficked antiquity on the international art market. Thousands of similar Maya vessels have suffered that fate. We would know absolutely nothing about the piece except what was on it: the information contained in the writing and the iconography. You see, it is a common assertion that there is still a lot of academic value left in looted antiquities, especially antiquities with writing on them. Collectors, dealers, museums and so on maintain that information recovered from trafficked cultural objects aids our understanding of the past. If that is the case, what would a reasonable scholar conclude about this vase?

- It was looted from the Guatemalan site of Naranjo. It is in the ‘Holmul-dancer’ style and Holmul is a site in Guatemala. Also the Guatemalan site of Naranjo is mentioned and everyone knows that Naranjo was torn to bits in the 70s and 80s by looters looking for pottery.

- It was used by a Naranjo ruler named Lord K’ak-Til since it says it was made for him.

- It perhaps came from Lord K’ak-Til’s tomb since Maya pottery is usually found in tombs, but we wouldn’t know that for sure.

- It perhaps held cacao beans at some point since it says that it did, but we likely would no longer be able to do scientific analysis on the piece since it was cleaned for sale on the market.

That’s it. We would assume we have K’ak-Til’s vase looted from Naranjo, Guatemala. End of story.

Analysis 2: The real story

We are lucky. This is one Maya vase that escaped the looting caused by international demand for illicit Maya ceramics. This pot is known as the Buenavista Vase as it was excavated by archaeologist Joseph W. Ball in 1988 at the site of Buenavista del Cayo, Belize. It was found in the spectacular tomb of an elite adolescent Maya male within structure BV-1, a pyramid at the site. The man was buried wearing jaguar fur mittens and booties and his body was covered with over 8000 obsidian blades.

The youth wasn’t Lord K’ak-Til. Buenavista is 35 kilometers away from Naranjo. The vase was found in Belize, not Guatemala.

Archaeologists now believe that Lord K’ak-Til had the vase made as a gift, a gift he gave to the ruler of Buenavista. It seems likely the gift was a memorial to the Lord’s dead son…the young man buried in the tomb. We can imagine a grieving father thanking Lord K’ak-Til, placing the beautiful piece in the tomb, and burying his son. We’d get none of that if the vase was looted. We’d still think it was stolen from Guatemala.

Everyone can visit the Buenavista vase in the Museum of Belize.

But wait, there’s more

For a hundred years the whole Maya region was embroiled in a vast and complicated war. A Maya ‘world’ war between city-states allied with the city of Mutul (now know as Tikal, in Guatemala) and the ‘Divine Lords of the Snake’ from Ox Te’ Tuun (now known as Calakmul, in Mexico). Naranjo was a large and powerful kingdom at the time but it, too, was swept into the war. In about 682 AD, Calakmul established a new ruling dynasty at Naranjo through a woman named Wak Chanil Ajaw (called Lady Six Sky before her name was able to be read). This meant that Naranjo was allied with Calakmul.

…and thanks to the Buenavista vase, we know that Naranjo was allied with Buenavista. The friend of my friend is my friend. We can now begin to speculate whether Calakmul’s influence during the war reached Buenavista, or maybe even that whole region of Belize.

The Buenavista vase is the only document we have that ties Buenavista to Naranjo and the only document that hints at a connection to Calakmul. With this one archaeological find we have expanded our understanding of Classic Maya sociopolitics with links that span three modern countries. We would have none of this if the vase had been looted.

Remember how I said thousands of looted Maya vases exist in international collections. Imagine all that we have lost.