Easter Week: the traditional time of grave robbing on Peru’s north coast.

2015 UPDATE: Archaeologists and volunteers are monitoring 500 archaeological sites in Lambayeque over Easter Week to try and prevent looting.

The Easter Week (Semana Santa) is particularly special to people in Latin America. In Peru people who live elsewhere travel to their home villages for this time of family, reflection, then celebration. But there is a dark side to this holiday: Easter Week is, traditionally, when huaqueros rob the ancient tombs of Peru’s north coast.

Over 90% of the famous archaeological sites of this region have been looted and it is clear that Easter is a troubled time for Peru’s past.

What is a huaquero?

A huaquero is a person who clandestinely excavates at archaeological sites for the purpose of obtaining marketable antiquities. The term is derived from the Quechua word ‘huaca’ (also ‘wak’a’). Prior to the Spanish Conquest, a ‘huaca’ was anything that was sacred with an emphasis on sacred places. Depending on the context, use of ‘huaca’ in modern times can imply that there is still a sacred quality to these sites and objects.

Today the term is most often ascribed to archaeological sites. In the form ‘huaco’, it normally, but not exclusively, means an ancient ceramic pot. A huaquero, then, is a person who illicitly excavates huacas (archaeological sites) for huacos (artefacts). The verb associated with huaqueros is ‘huaquear’: to illicitly dig at or loot an archaeological site.

One case Easter Week looting

Earlier this week a group of 5 looters destroyed 25 tombs in a Sicán culture cemetery at Cerro Campana. The looters were caught due to the increased police and archaeological monitoring of heritage sites during Easter Week. They were detected at 5pm on Holy Wednesday and had been looting the site since the night before. They fled from authorities, leaving tools and motorcycles behind, but police feel confident they will be able to identify the looters.

Why Easter?

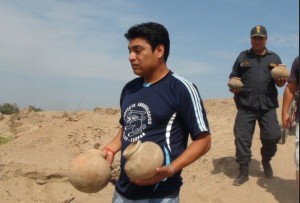

Officials and volunteers investigating Easter Week looting in 2011 via http://proyectoespecialnaylamp-lambayeque.blogspot.co.uk

There is a North Coast legend that during Easter Week artefacts come to the surface…that one barely has to dig for them. Some articles relate that Good Friday is the preferred day for looting because ‘God is dead and doesn’t watch‘. Other articles say that looting starts on Maundy Thursday when any outstanding curse that protects an archaeological site is lifted. Some believe that the pre-Conquest occupants of archaeological sites are non-Christian ‘Gentiles’ who, in a sort of raising of the dead sense, cluster near the surface only during Easter Week so that they may be found by Christians.

Archaeologist Walter Alva says that practice of Easter Week looting was introduced by the Spanish, who would have taken a large cut of whatever was looted. He believes that Easter looting has no foundation in pre-Conquest cultural tradition, but rather has been used as an excuse to rob graves. He notes that low-level Easter looters take all the risk and make nearly no money from the practice: only professional intermediaries tend to profit. I can’t help but liken that to the post-Conquest situation where Indigenous huaqueros would be lucky to keep even a sliver of the assessed value of the gold and silver they located.

Pots recovered during Easter Week looting investigations in 2011 via http://proyectoespecialnaylamp-lambayeque.blogspot.co.uk

It isn’t unreasonable to say that one of the main reasons looting happens during Easter Week is that everyone is off of work, they are back in the village, and they have time on their hands. It is when potential looters have time to loot.

In an interesting blog post, archaeologist Wilder León Azcurra relates that while he was a student in the 1970s, he and several friends decided to go looting in the Jequetepeque River Valley during Easter Week. They were young and naive and thought, perhaps, maybe the artefacts DO come to the surface as the legends say. They also had time on their hands.

They looted on land owned by a relative of one of the students. They used a metal rod which they poked into the surface and eventually found the supine burial of a man. Far from coming to the surface, they were forced to dig to loot this tomb. The Easter Week looting was his initiation into the world of archaeology and was the moment he realised how destructive looting really is.

Regulation: punishment and attitude change

Because the connection of looting to Easter Week is well-known, the potential to educate the public and regulate the practice during Easter is taken very seriously in Peru. The papers run reminders that the practice is illegal and warnings that the penalties for looting are steep. At the moment looters face up to 3 to 8 years in prison and there is some talk that this penalty will increase soon.

Guarding committees have been established that work with local police to monitor archaeological sites that are likely to be looted during Easter Week. These committees are not only made up of archaeologists and museum staff, but local residents and other volunteers. In other words, there is an increase in site protection and vigilance during Easter AND there is a concerted effort to involve and educate the public about protection of the ancient past.

Does this work?

It seems so. Walter Alva says that more than 3000 tourists will visit the Royal Tombs of Sipán museum during Easter Week alone. There they will not only experience new and exciting exhibitions about the history of Peru’s north coast, but they will learn the story of the looting of Sipán and the efforts made by Alva and others to save the site.

Alva believes that the practice of looting during Easter Week has gone into sharp decline. He sees this as both a result of increased protection of sites and because looting has been made socially unacceptable. Carlos Aguilar Calderon, the head of a Ministry of Culture unit devoted to the protection of archaeological sites, also believes that Easter looting is on the out. He says that the greatest threat to Peruvian sites in the region right now is from developers who level sites with heavy machinery and quarry them for construction fill.

Can the looting of an archaeological site be a cultural practice?

This is a very difficult question to answer, but it is not something that is unheard of. At times, living cultural traditions threaten a Western idea of heritage preservation. Modern use of an ancient site can slowly destroy it. Religious requirements that involve, for example, the burial or exposure of ancient cultural objects to the elements rub up against the idea of ‘cultural heritage of all humanity’ by allowing small groups to make what could (but maybe shouldn’t) be called destructive heritage preservation decisions. There is no easy road through this.

Indeed, this is where I face and embrace my most blatant hypocrisies. I might not tell you the same thing twice if you ask me what I believe.

Looting of archaeological sites permeates the culture of the North Coast. The vast majority of people don’t loot in any way and probably don’t know anyone who does, however huaquero mythology is everywhere. Looting in the area is filled with curses, spirits, riches, and legend. It is hard for anyone to resist. Everyone knows stories. I think one of the best ways to illustrate the place that the huaquero mythos occupies is via the Marinera Norteña ‘Huaquero Viejo’:

I am the old grave robber (huaquero)

and I have come to loot pottery (huacos)

from the highest ancient mound (huaca)

to the lowest to the lowest ancient mound (huaca)I had a cholita

Who was called Jacoba

And every night

The Barbacoba bird called (some versions say ‘barbacoa’, that isn’t original)Huaquero huaquero

Huaquero, were are going to loot (verb: huaquear)Coba coba coba at dawn

Coba coba coba at dusk

Bonus video of cute kindergarteners singing and dancing to the song. Notice the li’l ‘huaquero’ is even holding a little pot that he looted:

So looting runs deep in Peru, but looting is also destructive and unsustainable as a practice. The resource is finite and the gains are poor.

It seems like Walter Alva and the Peruvian authorities are on the right track. They have even made museum and site entry free during Easter Week. If Easter Week is a time when families are together and want to engage with their culture and their ancient past, it could be made into a time to visit local museums and sites without looting them.